This blog originally appeared on Business India.

Till early March, most global reports indicated that the number of cities in India with a population of more than 1 million, will grow from 42 to 68 by 2030. This equation may have altered considerably by June, due to the reverse migration of more than one crore workers to their village homes during the Covid-19 induced lockdown. Nevertheless, facing the constant threat of a mounting climate crisis, urban India has a chance to reboot and recover holistically, and ‘grow back greener’ in the post-Covid world.

The UN’s Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 11 emphasises the need for green and livable urban spaces. It sets targets for enhancing urban green by 2030, as a means to secure resources, reduce pollution and increase resilience. Nature-based solutions are fast emerging as a way of addressing sustainability challenges and building urban resilience. Planting trees is the easiest means to preserve and restore natural capital at scale.

Given that the ecological and environmental benefits of trees are well-known (recent literature also points to social cohesion and crime reduction benefits), several cities in India are calling for building urban forests to help offset climate change, improve air quality, reduce urban heat island effects and provide healthy and livable neighborhoods.

On World Environment Day (5 June), the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) launched the Nagar Van Scheme to develop 200 urban forests across India in the next five years, complementing the Biodiversity Vision declared by the UN. The participatory model with which the urban forest garden project at Warje, Pune, was established and is maintained was lauded and highlighted as the way forward, along with examples of initiatives in Hyderabad and Delhi. However, most of these models focus on large tracts of land (16 hectares in Warje), a hugely constrained resource in urban areas. However, there are other significant interventions to achieve greening by communities in land-limited urban cores, which would impact the micro-climate and provide a healthier, resilient and livable environment in the long-term.

Five opportunities for enhancing urban green at the neighborhood level:

- Community/home-gardens/rooftops: This is the simplest way by which a city dweller can enhance the community green cover. Examples of this are sacred groves, one of the oldest practices for greening neighborhoods where members of the community take turns to protect forest fragments which are rich ecological gene pools. The size of sacred groves can vary anywhere between 0.04 to 10,000 hectare; to modern day agrihoods (less than two acres to more than 20 acre farms), which are centered on farming. This type of engagement not only leads to greater environmental consciousness but can also be a step towards food security and wellbeing.

- Avenue planting: Planting trees along streets for shade, visual relief and aesthetics, is a common practice worldwide, however, it is mostly restricted to places where there is adequate right-of-way (a minimum sidewalk width of 6.5 to 7.5 feet). A significant element of complete streets are planting strips. The shade from trees can not only modulate the local microclimate and reduce air pollution), but also lend permeability to the soil, acting as sponge during flooding. There needs to be a conscious shift within urban local bodies, particularly transport and land development departments, towards designing green streets, such that every right-of-way incorporates planting zones suited to the environment, scale and level of maintenance.

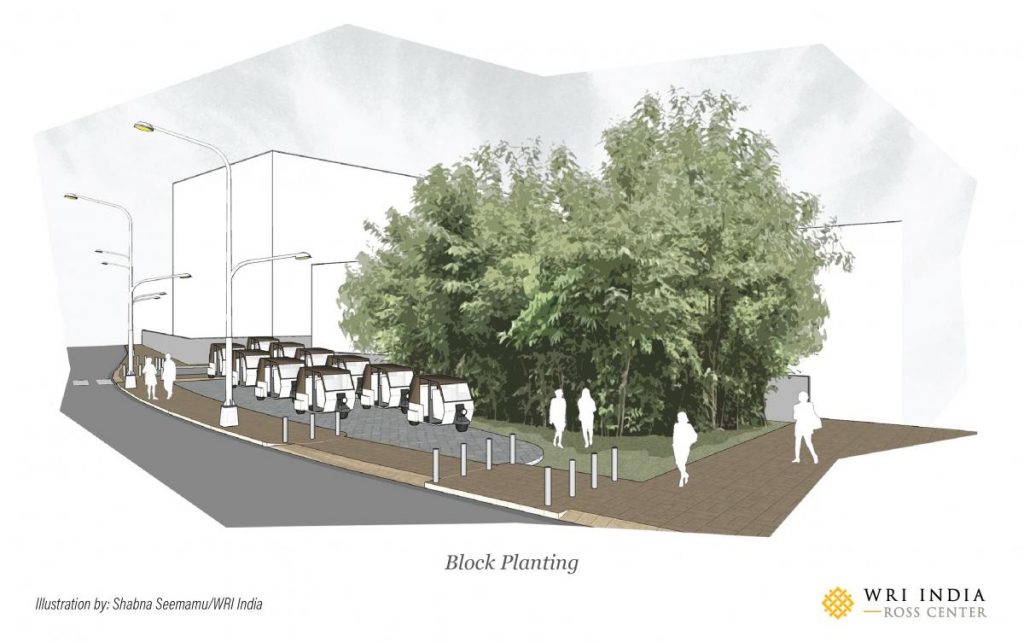

- Block planting: This is a method of maximising planting in a given area by reducing the traditional spacing between plants. The Miyawaki method of tree planting has gained popularity among Indian city corporations as a means to augment urban tree cover and provide spaces for biodiversity conservation. This is a unique method to add patches of greenery to any neighborhood. Requiring small/residual plots (minimum 20 sq. feet) such planting needs little maintenance after a couple of years. This method, though a successful effort towards greening, must be implemented with caution to ensure ecological integrity.

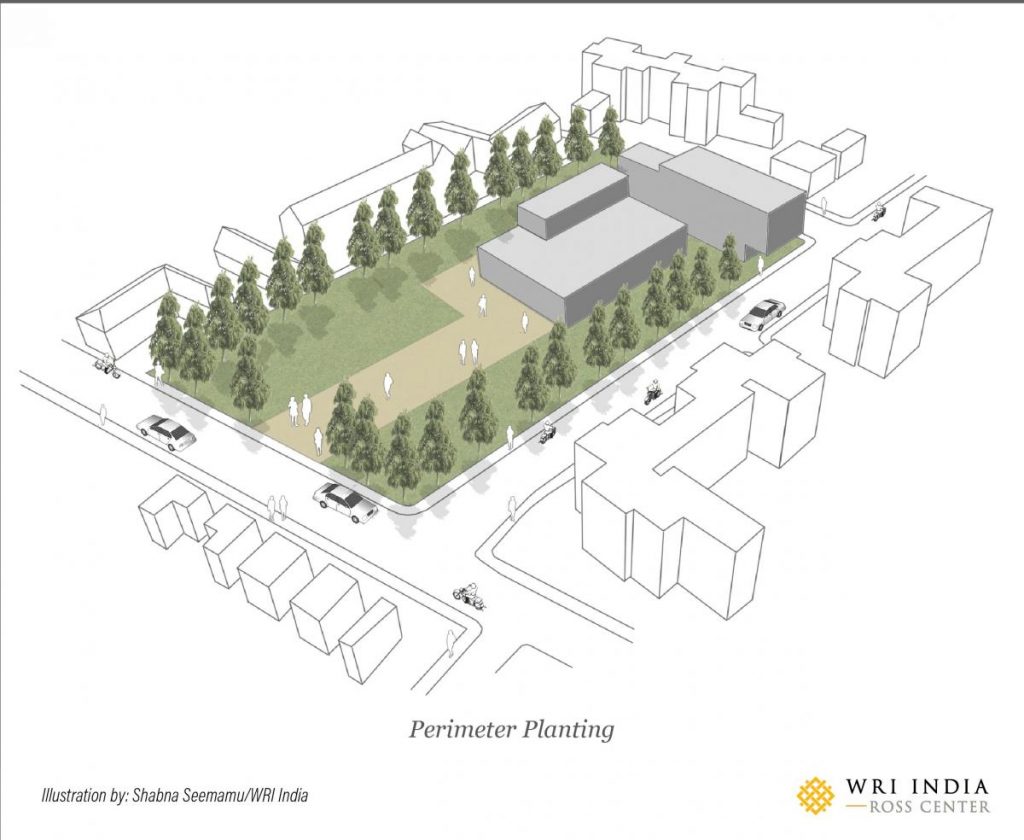

- Perimeter planting: This type of planting, done along or in place of boundary walls, is mostly used for screening plots, noise reduction, and good airflows. This method requires three feet average width on the street for creating buffers. Desirable for schools and hospitals, the planting is in staggered rows or clusters depending on the availability of space and preferred aesthetics. This is a practical way of increasing tree-cover and can be pursued through building norms, with allowances made for utility lines, walkways, driveways, and roads that must remain visible and accessible.

- Waterways/riparian planting: Planting around waterbodies preserves the sanctity of wetlands and stabilizes the land, while ensuring their sustainability. This requires identifying appropriate vegetation, soil conditions and establishing margins so that the waterways are not impacted adversely. Riparian planting can also act as buffers that moderate water flow, as filters for pollutants and provide corridors linking habitats for native species of flora and fauna. The plant species need to be selected carefully and planting needs to be managed and monitored consistently to achieve optimal environmental and developmental benefits.

Urban Forest Management

Neighborhood-level greening can yield localized yet significant benefits to human health and wellbeing. However, ensuring the sustainability of green cover in urban areas entails a few conditions be met. First, a robust baselining of ecological and environmental factors, such as soil type, drainage, soil acidity, etc., that help understand local conditions, planning, setting reasonable targets, and monitoring, is essential. Second, maintaining ecological integrity which requires an understanding of species, space, land-use norms, and availability of water, to prevent negative consequences from improper plantations. Also, geo-climatic, socio-economic, and cultural conditions will need to be factored in. Finally, operational effectiveness in planting and maintenance needs to be evaluated to draw up a plan that outlines procedural protocols and responsibilities of various stakeholders. A transparent, multi-stakeholder approach in the planning, management, cost-sharing mechanisms, and accountability would enable the sustenance of urban forests.

Urban forests can offer many benefits to people. Robust and equitable urban forest management policies and incentives are needed to enable scaling and widespread access to such greenery. Along with technical know-how, inclusion and participation are pivotal to their success.

Views expressed are the authors’ own.