The second blog in our two-part blog series illustrates four pilot community based ‘Nature-based Solutions’ (NbS) interventions in Jaipur that address climate induced heat stress and water scarcity. The first blog in the series introduced the context for the project and, highlighted five key strategies for implementing NbS in the city.

India experienced almost one extreme weather event per day in the first nine months of 2022. Rajasthan is no stranger to this conversation with its capital city of Jaipur ranking 22nd on the global climate vulnerability index. One viable way of addressing the impact of extreme climate events is through Nature-based Solutions (NbS). To this end, WRI India, under the Cities4Forests initiative, piloted nine NbS interventions informed by the local climate profile, context, and the corresponding climate induced risks for Jaipur.

In this blog, we will be discussing four of these interventions.

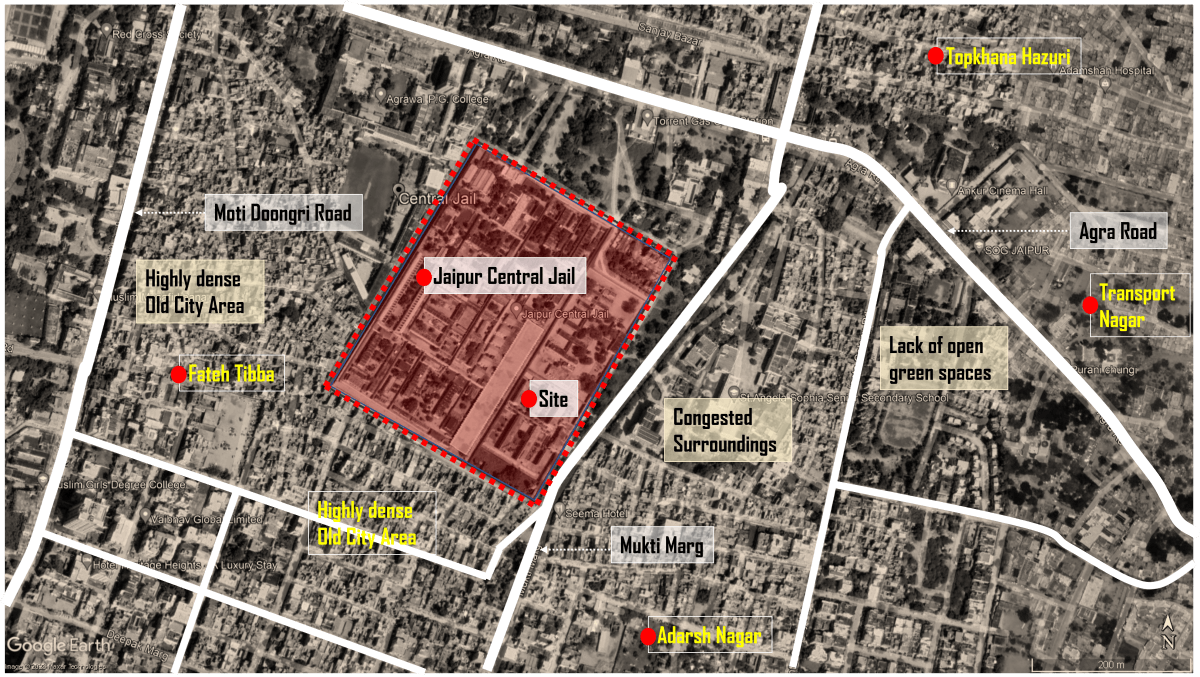

Urban Farming at Jaipur Central Jail

The Jaipur Central Jail is an 18-acre facility located in the heart of the city with barren parcels of land situated within the complex. Owing to its low green cover, and its proximity to areas with high urban density, the campus experiences extreme heat stress during the summer months.

Our team decided that urban farming could serve as a two-fold solution – addressing urban heat and ensuring food security within the campus. Training selected inmates on developing and maintaining the urban farm also enhanced their skills and future employability. This initiative increased inmate access to green spaces while providing organic food to over 1000+ inmates and jail officials.

This project proved so popular that the involved inmates, due for release, are now training their fellow inmates to take over maintenance responsibilities thus ensuring the long-term success of the urban farm. The Rajasthan State Prison Department is exploring avenues to replicate this program’s success to other prisons across the state. https://flo.uri.sh/visualisation/15382523/embed

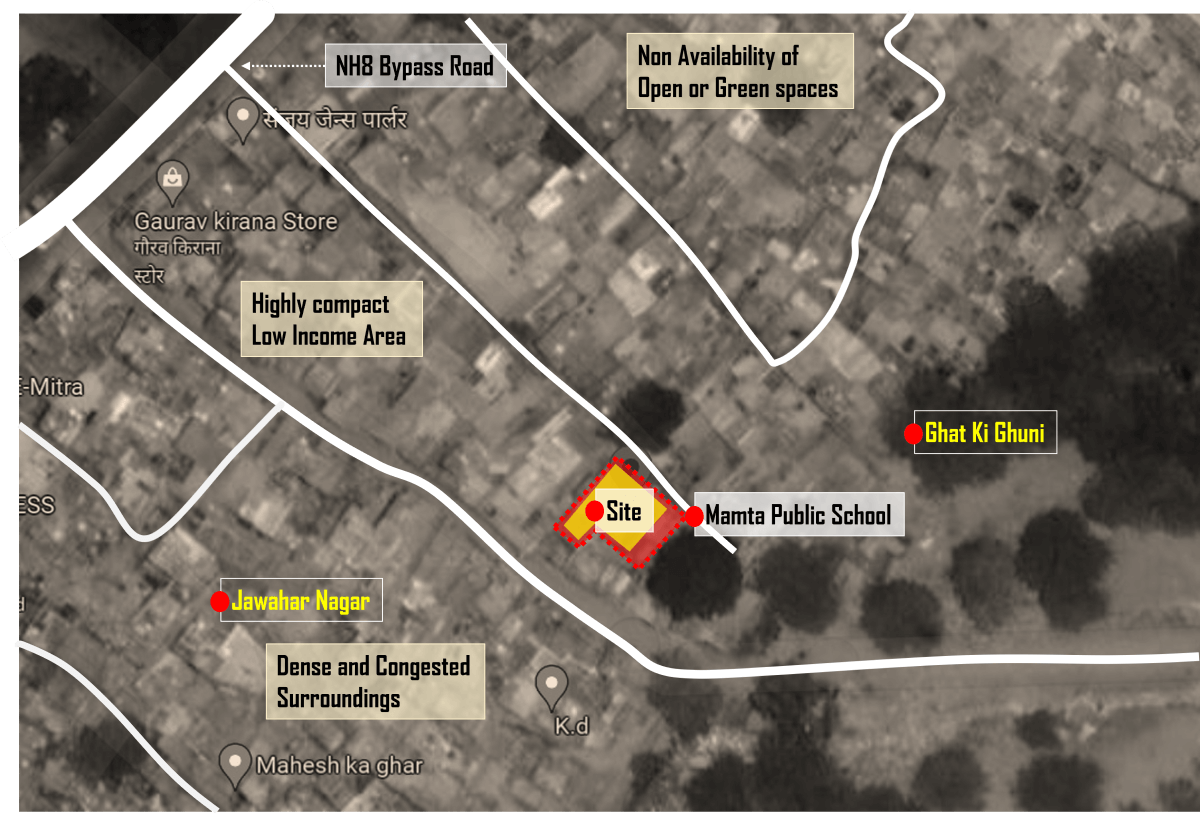

Rooftop Farming at Mamta Public School

A community institution situated in a densely built, low-income settlement within the city, Mamta Public School has limited access to greenery and open spaces.

The school building experiences intense heat during the summer months because of its exposed rooftop. In this case, the team opted for rooftop farming to mitigate heat and additionally provide food security to community members.https://flo.uri.sh/visualisation/15382511/embed

The school authorities played a key role in convening multiple stakeholders. We engaged with community residents, students and their parents through a workshop and created a community farming group to explore rooftop farming at other locations in and around the school.

Versha, a resident of this community, best describes the difference this made, “Back in my village where I grew up, I ate fresh fruits and vegetables that we grew in our backyard and the fields nearby. The small houses and limited space in the city do not allow us to do that anymore. This rooftop farm is allowing me to do what I miss so much!”

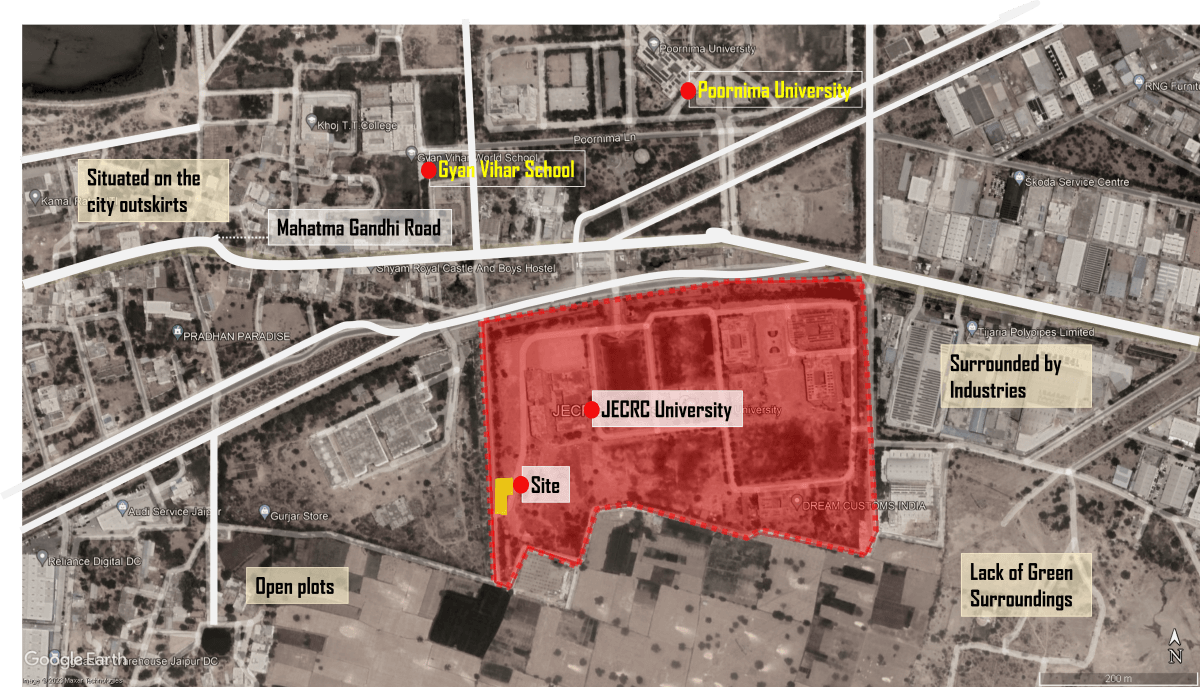

Urban Forest at JECRC University

The Jaipur Engineering College and Research Centre (JECRC) University campus, located in the city’s outskirts, witnesses high land surface temperature due to inadequate vegetation and barren land parcels around it.

Developing urban forests was recognized as an effective strategy towards heat mitigation and micro-climate regulation.https://flo.uri.sh/visualisation/15391773/embed

We got the unique opportunity to work with a student-led greening initiative that helped us leverage critical skills needed for implementation, monitoring and maintenance of the planted saplings. The students were introduced to the impact of climate change and NbS, and the different careers in the climate and sustainability sector. Additional opportunities towards building heat resilience in the campus, such as rooftop and urban farming were also identified, and their implementation strategies were explored.

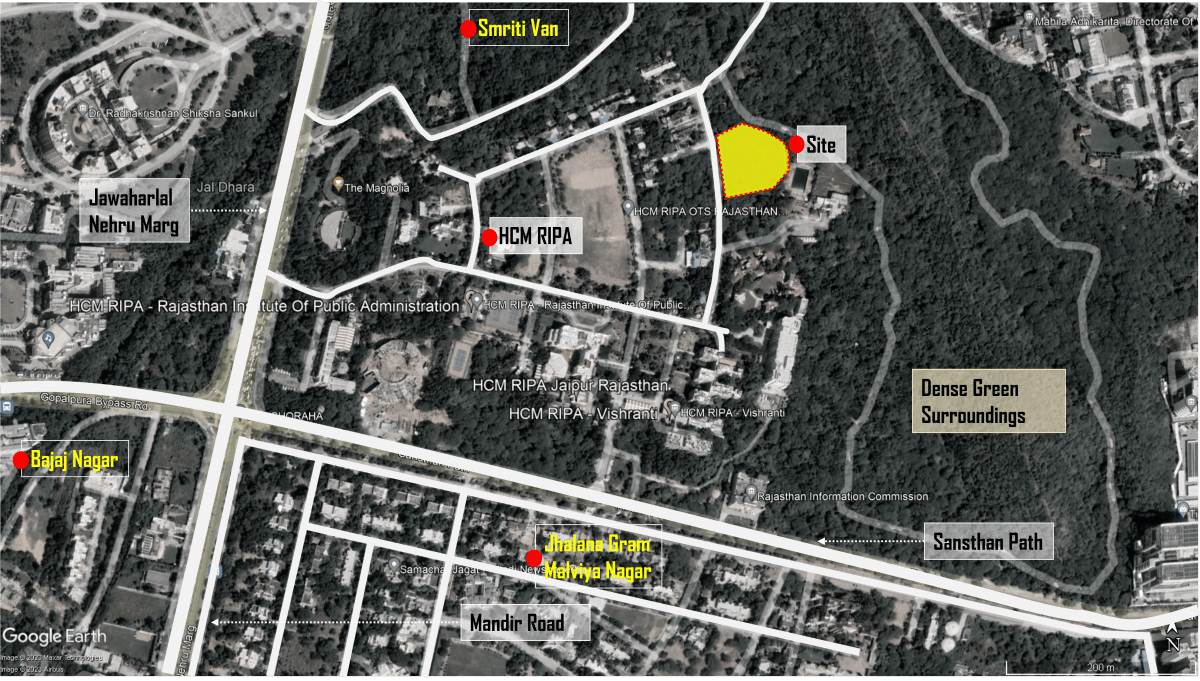

Water Body Intervention at Harish Chandra Mathur Rajasthan State Institute of Public Administration (HCM RIPA)

The state training institute, located along the city’s forest reserve area, offered the potential to mitigate urban heat and improve subsurface water recharge, owing to the natural advantage of the terrain.

We identified an existing trench and restored it as a seasonal water body. Employing indigenous materials and plant species, we connected with local community members to integrate their knowledge and practices of indigenous water conservation practices.https://flo.uri.sh/visualisation/15382527/embed

Additionally, the area encircling the waterbody was developed as an urban forest to minimize soil erosion, regulate the microclimate, and improve local biodiversity. This intervention was demonstrated as an NbS proof of concept through a knowledge sharing workshop attended by over 90 administrators.https://flo.uri.sh/visualisation/15382546/embed

Our experience of having worked in Jaipur indicated that currently there is a general preference for grey-infrastructure oriented solutions – i.e. human-engineered traditional approaches to water management such as storm water drains. Through these interventions, we sought to build evidence and strengthen the case for hybrid infrastructure (blue-green-grey) and NbS amongst the city’s stakeholders.

These four pilot programmes were not just limited to identifying local challenges and opportunities for NbS interventions. We also aimed to integrate local and indigenous knowledge for more robust outcomes. While these initiatives have laid the groundwork for NbS in Jaipur, its potential for large-scale action lies on its adoption and inclusion within the urban development framework.

All four pilots showcased in the blog were anchored by WRI India and Living Greens Organics Pvt. Ltd. in collaboration with the Caterpillar Foundation under the Cities4Forests initiative.

All views expressed by the authors are personal.

AUTHOR:

Himanshi Kapoor – himanshi.kapoor@wri.org

Siddharth Thyagarajan – siddharth.thyagarajan@wri.org